Navigating the World of Diets: A Research-Based Guide to Popular Eating Plans

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of a qualified healthcare professional, such as a doctor or registered dietitian, before making any significant changes to your diet or health regimen.

I. Introduction

In today’s health-conscious world, the term “diet” is often mistakenly viewed as synonymous with temporary, restrictive weight loss measures. Fundamentally, a diet simply refers to the sum of food and drink regularly consumed by a person. Beyond fleeting fads, many structured eating plans are underpinned by robust scientific research, offering potential benefits that range from improved metabolic health and disease prevention to enhanced longevity and overall well-being.

With a complex landscape of options available—from ancient eating patterns to modern nutritional strategies—understanding the core principles, supporting evidence, and necessary considerations of each is paramount for making informed personal choices. This comprehensive, research-based article will explore several prominent dietary approaches, examining their core tenets, scientific support, potential advantages, and key factors for safe and effective adoption. Our goal is to provide a balanced, evidence-informed overview to help you navigate this diverse world of nutrition.

II. Foundational Nutritional Science

Any sustainable and effective dietary approach must respect the fundamental principles of human nutrition. The body requires a balance of macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) to function optimally. Weight change, regardless of the diet chosen, ultimately relies on the energy balance equation: energy intake versus energy expenditure. Furthermore, the focus should always be on nutrient density—choosing whole, unprocessed foods that deliver a high amount of nutrients relative to their calorie count. Neglecting these basics in favor of overly restrictive or unbalanced plans is often a recipe for short-term failure and long-term health risks.

III. The Mediterranean Diet: The Longevity Leader

The Mediterranean Diet is less a strict regimen and more a traditional, geographically inspired eating pattern historically followed in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. It is consistently ranked among the healthiest diets globally due to its strong backing by decades of research.

Core Principles and Science

This diet emphasizes an abundant intake of plant foods (fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds, legumes) and relies on Extra Virgin Olive Oil as the primary source of fat. Fish and seafood are eaten frequently, poultry and dairy in moderation, and red meat and sweets are minimal. The health benefits are largely attributed to the diet’s strong anti-inflammatory profile, which stems from the high intake of monounsaturated fats (from olive oil) and antioxidants (from diverse plant sources).

Research and Benefits

The most compelling evidence comes from large-scale studies, notably the PREDIMED trial, which linked the diet—especially when supplemented with nuts or olive oil—to a significant reduction in the risk of major cardiovascular events (heart attack, stroke, death) in high-risk individuals. The diet is also associated with reduced risk of Type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, and improved cognitive function, making it a highly sustainable approach for promoting longevity and well-being.

IV. The Ketogenic (Keto) Diet: The Metabolic Shift

The Ketogenic Diet is a very low-carbohydrate, high-fat, and moderate-protein approach that fundamentally shifts the body’s primary fuel source.

The Mechanism of Ketosis

By drastically limiting carbohydrate intake (typically to 20–50 grams per day), the body is forced to enter a metabolic state called ketosis. When glucose stores are depleted, the liver breaks down fat into ketone bodies, which the body (including the brain) uses for fuel.

Research and Application

Keto was originally developed in the 1920s as a therapeutic diet for children with refractory epilepsy, a use that remains scientifically proven. More recently, studies have explored its efficacy for rapid weight loss and its potential for improving insulin sensitivity and blood sugar control in some individuals with Type 2 diabetes.

Cons and Necessary Warnings

While effective for short-term goals, the Keto diet is highly restrictive and often difficult to sustain. Adherence can lead to the “keto flu” (fatigue, headache, nausea) as the body adapts. Crucially for policy compliance: It is not suitable for everyone, particularly individuals with certain gallbladder, pancreatic, or liver conditions, or pregnant/breastfeeding women. Long-term safety data is still limited, and the diet requires careful planning to prevent deficiencies in fiber and certain micronutrients.

V. Plant-Based Diets: Vegetarianism and Veganism

Plant-based eating encompasses a range of diets, including Vegetarianism (which excludes meat, poultry, and fish but often includes dairy and eggs) and Veganism (which excludes all animal products). These diets are typically motivated by ethical, environmental, and health concerns.

Health Benefits and Science

Research consistently shows that plant-based diets are associated with a lower risk of heart disease, hypertension, and Type 2 diabetes compared to omnivorous diets. This is often attributed to a higher intake of fiber, vitamins, antioxidants, and phytonutrients, and a generally lower intake of saturated fat and cholesterol.

Critical Considerations and Planning

While beneficial, plant-based diets—especially veganism—require careful nutritional planning. Vitamin B12 (found almost exclusively in animal products) must be supplemented on a vegan diet. Other nutrients, such as Iron, Calcium, Vitamin D, and Omega-3 fatty acids, must be actively sourced from fortified foods or supplements to prevent deficiencies. A poorly planned plant-based diet that relies heavily on processed substitutes can be just as unhealthy as a poor omnivorous diet.

VI. The Paleo Diet: The Ancestral Approach

The Paleolithic (or Paleo) Diet is based on the premise that modern humans should eat like their Stone Age ancestors, arguing that the human digestive system has not fully adapted to foods introduced after the agricultural revolution.

Core Principles

The diet emphasizes lean meats, fish, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds, while strictly excluding grains, legumes, dairy, refined sugars, and processed foods.

Research and Practicality

Studies have shown that Paleo can lead to weight loss and short-term improvements in glucose tolerance and lipid profiles. However, it is one of the more restrictive eating patterns. The exclusion of entire food groups, such as whole grains and legumes (which are rich in fiber and essential nutrients), is nutritionally controversial. Furthermore, the diet can be expensive and may present a challenge for meeting calcium requirements due to the exclusion of dairy.

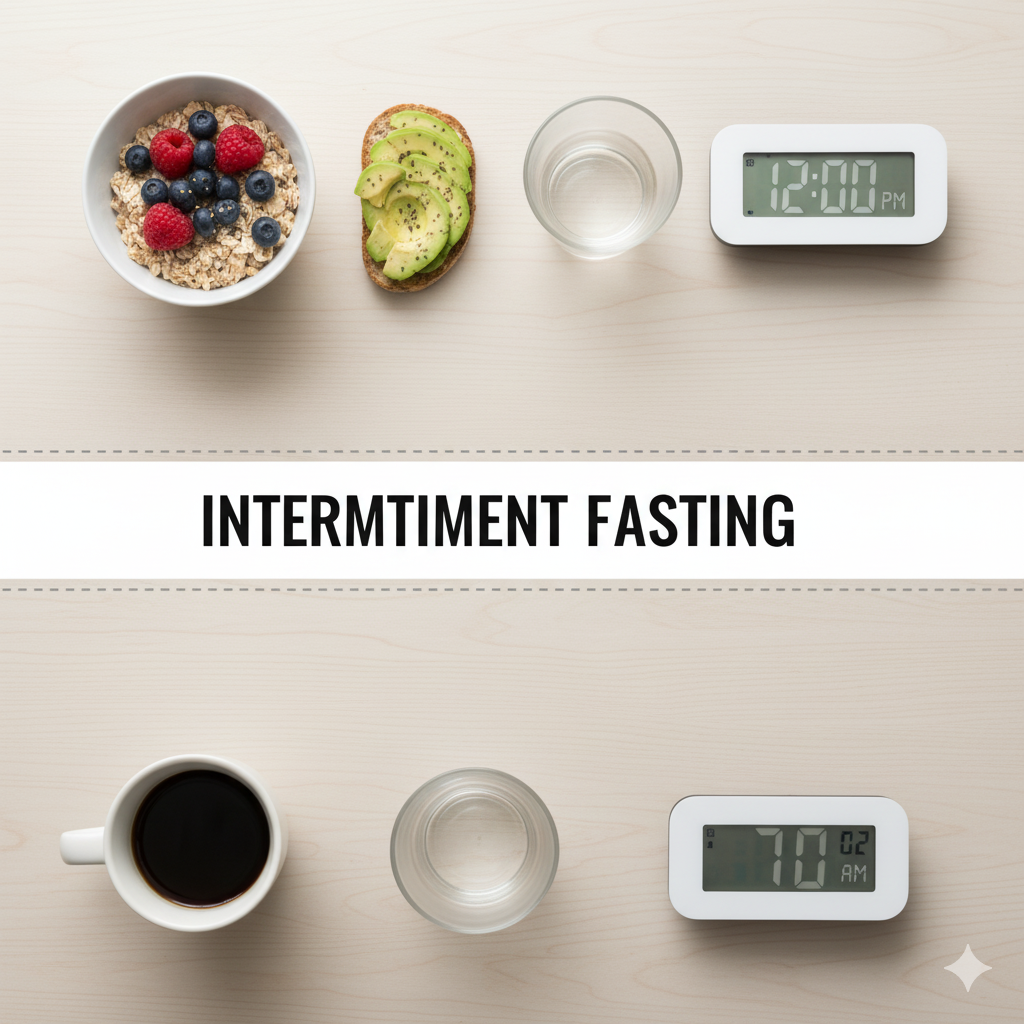

VII. Intermittent Fasting (IF): The Eating Pattern

Intermittent Fasting (IF) is not a diet in the traditional sense, but rather a structured eating pattern that cycles between periods of voluntary eating and fasting. Popular methods include the 16/8 method (fasting for 16 hours, eating during an 8-hour window) and the 5:2 method (eating normally for 5 days, severely restricting calories on 2 non-consecutive days).

Proposed Mechanisms and Research

The supposed benefits of IF go beyond simple calorie restriction. Research suggests IF may improve insulin sensitivity and initiate cellular repair processes, known as autophagy. It has shown efficacy for weight management and metabolic marker improvement in various human trials.

Important Warnings

While simple, IF is not for everyone. It is strongly discouraged for individuals who are pregnant or breastfeeding, those with a history of eating disorders, or people taking certain medications that must be consumed with food. Individuals may experience initial side effects like fatigue, irritability, and headaches, and there is a risk of overeating during the designated feeding window.

VIII. Conclusion: The Personalized Approach

The vast landscape of diets confirms a fundamental truth: there is no single “best” diet that works for every person. The scientific evidence supports several distinct paths to improved health, provided the approach is nutritionally sound and sustainable.

Whether following the heart-healthy, flexible pattern of the Mediterranean diet, the restrictive metabolic shift of Keto, or the nutrient-dense framework of a plant-based plan, the most crucial factors remain constant: a focus on whole, unprocessed foods, adequate hydration, and consistent physical activity.

Ultimately, the best diet is the one that is sustainable, nutritionally adequate, supports individual health goals, and aligns with one’s lifestyle and personal preferences. Before embarking on any major dietary change, especially if you have pre-existing health conditions, the counsel of a qualified healthcare professional or registered dietitian is paramount to ensure the chosen path is safe and effective for your unique body.

Tools